A discussion, today, reminded me of this excerpt, from G.K. Chesterton’s, What’s Wrong with the World:

This book must avoid religion, but there must (I say) be many, religious and irreligious, who will concede that this power of answering many purposes was a sort of strength which should not wholly die out of our lives. As a part of personal character, even the moderns will agree that many-sidedness is a merit and a merit that may easily be overlooked. This balance and universality has been the vision of many groups of men in many ages. It was the Liberal Education of Aristotle; the jack-of-all-trades artistry of Leonardo da Vinci and his friends; the august amateurishness of the Cavalier Person of Quality like Sir William Temple or the great Earl of Dorset. It has appeared in literature in our time in the most erratic and opposite shapes, set to almost inaudible music by Walter Pater and enunciated through a foghorn by Walt Whitman.

But the great mass of men have always been unable to achieve this literal universality, because of the nature of their work in the world. Not, let it be noted, because of the existence of their work. Leonardo da Vinci must have worked pretty hard; on the other hand, many a government office clerk, village constable or elusive plumber may do (to all human appearance) no work at all, and yet show no signs of the Aristotelian universalism. What makes it difficult for the average man to be a universalist is that the average man has to be a specialist; he has not only to learn one trade, but to learn it so well as to uphold him in a more or less ruthless society.

This is generally true of males from the first hunter to the last electrical engineer; each has not merely to act, but to excel. Nimrod has not only to be a mighty hunter before the Lord, but also a mighty hunter before the other hunters. The electrical engineer has to be a very electrical engineer, or he is outstripped by engineers yet more electrical. Those very miracles of the human mind on which the modern world prides itself, and rightly in the main, would be impossible without a certain concentration which disturbs the pure balance of reason more than does religious bigotry. No creed can be so limiting as that awful adjuration that the cobbler must not go beyond his last. So the largest and wildest shots of our world are but in one direction and with a defined trajectory: the gunner cannot go beyond his shot, and his shot so often falls short; the astronomer cannot go beyond his telescope and his telescope goes such a little way. All these are like men who have stood on the high peak of a mountain and seen the horizon like a single ring and who then descend down different paths towards different towns, traveling slow or fast. It is right; there must be people traveling to different towns; there must be specialists; but shall no one behold the horizon? Shall all mankind be specialist surgeons or peculiar plumbers; shall all humanity be monomaniac?

Tradition has decided that only half of humanity shall be monomaniac. It has decided that in every home there shall be a tradesman and a Jack-of-all-trades. But it has also decided, among other things, that the Jack-of-all-trades shall be a Jill-of-all-trades. It has decided, rightly or wrongly, that this specialism and this universalism shall be divided between the sexes. Cleverness shall be left for men and wisdom for women. For cleverness kills wisdom; that is one of the few sad and certain things.

But for women this ideal of comprehensive capacity (or common-sense) must long ago have been washed away. It must have melted in the frightful furnaces of ambition and eager technicality. A man must be partly a one-idead man, because he is a one-weaponed man—and he is flung naked into the fight. The world’s demand comes to him direct; to his wife indirectly. In short, he must (as the books on Success say) give “his best”; and what a small part of a man “his best” is! His second and third best are often much better. If he is the first violin he must fiddle for life; he must not remember that he is a fine fourth bagpipe, a fair fifteenth billiard-cue, a foil, a fountain pen, a hand at whist, a gun, and an image of God.

The frustration of not being an expert

I read that, in my early 20s, stumbling across the late, great Chesterton, while trying to decide if marriage is my proper vocation (and then immediately reading all of his nonfiction, as it’s all so brutally, casually, brilliant). It immediately made my own “talent stack” clear to me: I’m best at doing lots of different things quite well, but not at doing one particular thing to a level of highest expertise.

This is actually an extremely difficult position to be in because young people are under constant pressure to find That One Thing that they are to specialize in, and I could never find That Thing, despite being at the top of any ranking of People Doing Things.

Could I write well? Yes. Could I write really well? Yes. Could I write really, really well? Nope.

Could I program well? Yes. Could I program really well? Yes. Could I program really, really well? Nope.

Could I cook well?…

And so on, and so forth, for nearly every task I tried. Perpetually stuck in the upper quintile, never a top-tenner.

Much has been written about chronic Imposter Syndrome among the very-smartest women, but I think that’s just a fancy way to explain this phenomenon of being at the top of your game and atop all of the other women playing the same game, but quickly discovering, to your dismay, that the men at the top are a wee bit topper than you. And there’s always one a wee bit topper. There must be an endless supply of men-slightly-better at That One Thing, someplace. A factory, where they are produced by dark forces, like the Orcs, in The Lord of the Rings.

It is enough to make a girl pout, very cutely.

Titles matter

I’ve written, before, about how I see my development role as being the project teams’ “Girl Friday”. I pick up all the tasks that fall to the wayside, but shouldn’t be forgotten (like marketing, testing, arranging financing, and customer support), or substituting for someone who is away. Although men and women are partially redundant, so that there’s a Boy Friday for every Mrs. Burns, it seems clear to me that humanity really is generally split up into these specialist/generalist roles.

Women tend toward generalism, but often no longer have a natural outlet for it, so many of us are therefore in a state of employment frustration. We cling to various titles, without fully identifying with them. Drifting from one title to another. Earning a new title. Going off to find ourselves. Earning another new title. No, this one also doesn’t fit… Seeking, but never finding. The incongruence and impermanence can be painful. Aimless drifting.

Stacking up certificates and qualifications, but immediately bored by the myopic scope of the task and – if we’re in a male-dominated trade – frustrated by our difficulty in topping The Toppers; struggling to find some niche, some branch, where our generalism is an advantage.

Life is unfair. Boys are mean. Someone do something.

There used to be a specialty for generalists

But someone had done something. A long, long time ago. In fact, we are generalists today because of what that one woman did, back then: she married.

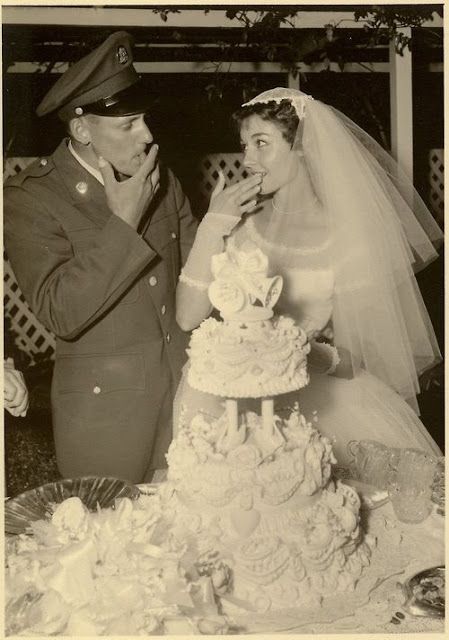

The bride is the star of every wedding and being a wife often brought a change in title (from Miss to Mrs.) because it is meant to be a vocation. It is as if you have been hired to be the household generalist, by the specialist, whose title reflected his particular specialty. If you actively joined in his specialty, it would simply be tacked onto your original title “Miller’s Wife”, “Lawyer’s Wife”, “Politician’s Wife”, “Farmer’s Wife”, “Engineer’s Wife”, “Butcher’s Wife”, “Bitcoin Influencer’s Wife”. (Angela Merkel’s spouse had the title “Chancellor’s Husband”, but the construction remains.)

The point of all of this, was to build mixed-sex pairs, with overlapping skillsets, with one generalist and one specialist. This was a solid construction, for millions of years. Turning the tasks of the generalist into a series of professions, in order to financialize and tax the output, undermined the core concept of marriage by eroding its value-added to the participants. That is why marriage is now often seen exclusively as a romantic, long-term-fling, rather than the practical and efficient basis of any sustainable family and economic system.

Marriage is about the economy, stupid

That is why marriage equality became such a hot topic, in the 90s. If marriage is just about hanging about in the house with someone you find attractive (i.e. “roommates with benefits”), rather than the basic building block of society, then why shouldn’t everyone doing that be considered married? Then everyone could have the same status, as married people did. This was a logical argument that won because society had completely abandoned the counterargument: Marriage isn’t that.

Marriage was a specific construct to serve a specific purpose with maximum efficiency and efficacy. Society honored it because everyone benefitted from people engaging in it, even if they themselves did not. Society didn’t honor marriage because it was good for the people in it; they honored it because it was good for everyone else.

Because, within marriage, there is room for a Jill-of-All-Trades, and the people outside of the marriage don’t have to pay for her labour or subsidize her retirement, at the same time that they profit indirectly from it.

But, the generalist wife is not the star of the entire world, she’s the star of one particular man’s world, and for many women, that world was simply too small. They needed a bigger stage to perform on.

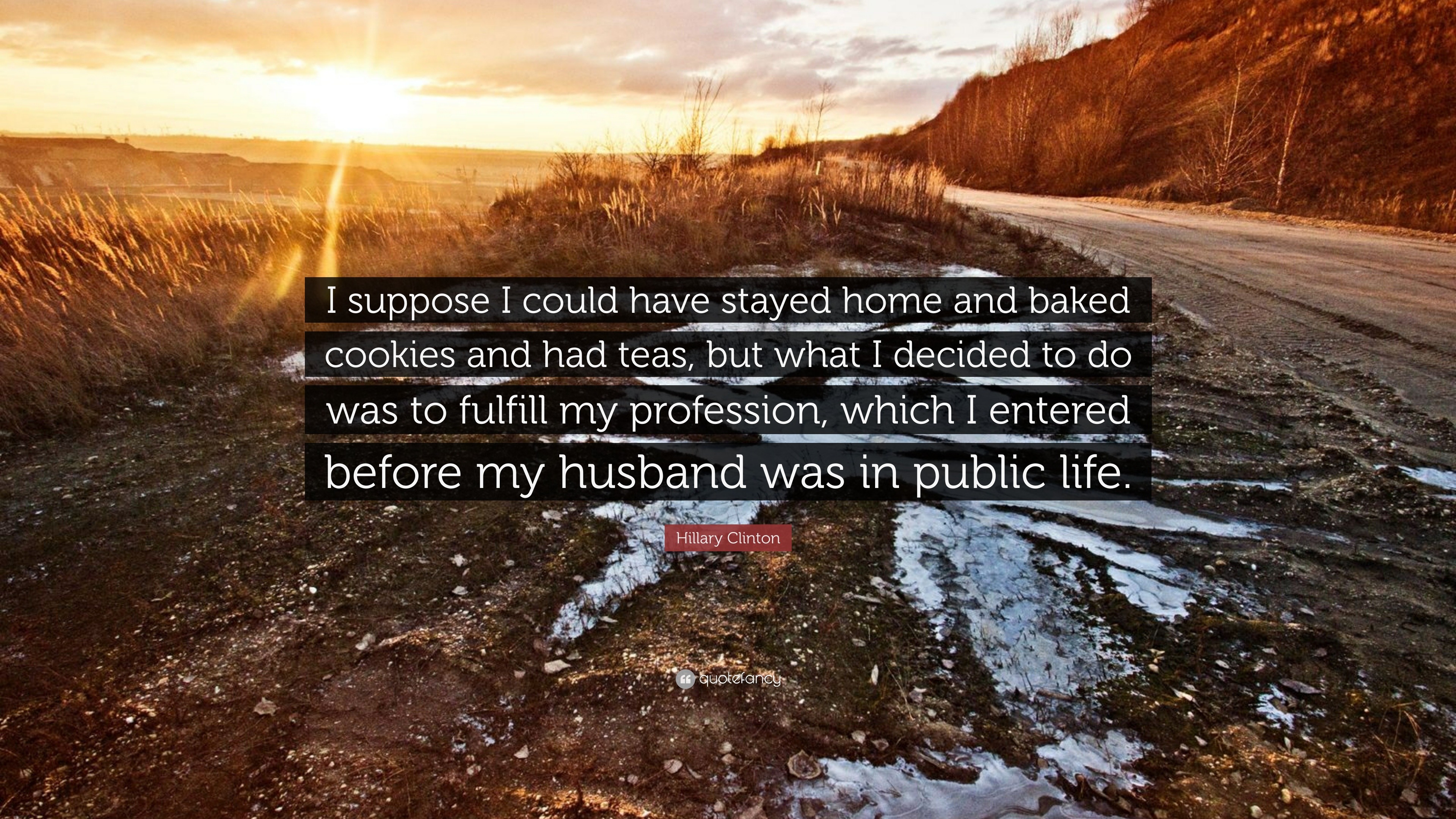

Even being The President’s Wife isn’t title enough, for some, when they hungered to hold The President title, directly.

The consequent and purposeful destruction of the marital institution – and the denegration of generalism, that necessarily went along with it – is, I am convinced, the reason that we can’t have nice things. And it’s the reason why women gaining power hasn’t lead to their increased happiness or more-stable and fruitful families.

In the end, a specialist title isn’t enough, for most of us. What we want most, is to be loved and honored and cherished for what we are. And we are generalists.

And that is why I chose to stay home and bake cookies. In this little house, in our home economy, I am the best cookie baker because I am a good-enough cookie baker. I only have to be good-enough.