The Australian dream used to be straightforward: secure a job, pay off your house by your late thirties, and retire with substantial assets and savings to support your lifestyle.

Some argue the introduction of compulsory superannuation contributions in 1991 signaled the government’s lack of trust in Australians’ ability to save and be self-sufficient in their later years. But I disagree.

The issue wasn’t that Australians were incapable of saving; it was that saving money was no longer enough. The erosion caused by the Keynesian experiment had seeped into Australian retirements, making it nearly impossible for an entire generation to retire off the savings from a median salary of $27,200.

Superfunds were thus established by the government as a supposed solution to the problem they had created. How unsurprising.

Fast forward 33 years, and Australian superfunds, like those in most of the western world, are now facing two insurmountable challenges of population demographic, and a debasing currency.

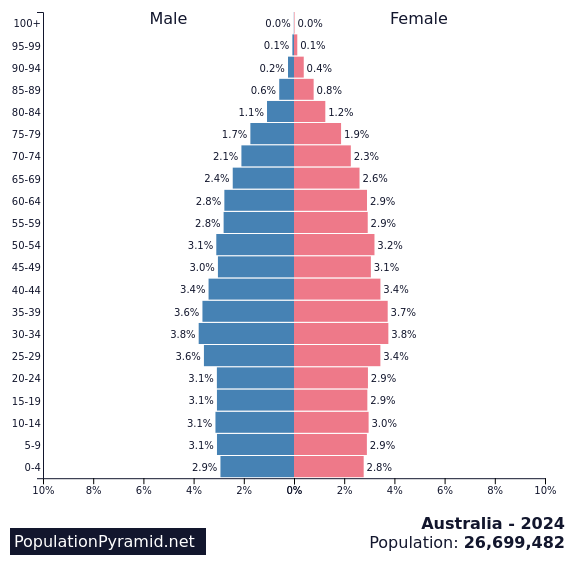

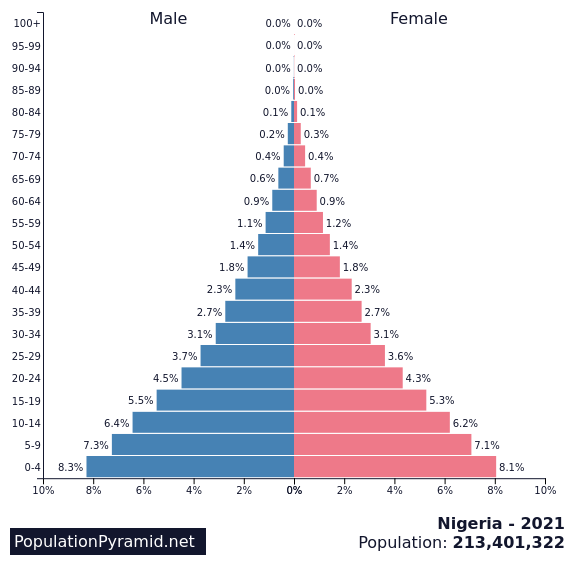

1. Our Population is Ageing

On face value, it shouldn’t matter whether the population is ageing. If I have my own retirement account which I paid into each month, why would it matter if the people around me are ageing as well?

The answer lies in duration mismatch. Retirement funds must manage a mix of short-term, long-term, and continuous obligations, balancing liquid liabilities (cash payments to members) with illiquid assets (investments). Because funds rely on more inflows (super contributions) than outflows (payouts to retirees), population demographics play a critical role in maintaining this balance - and Australia’s isn’t looking great.

An example of an ageing population (Australia) vs a growing population (Nigeria)

2. Our Currency is Ever Debasing

This is far more pernicious for our retirees

| Financial Year | Average Super Return | Money Supply Growth | Net Return |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2023-24 | 9.1% | 4% | 5.1% |

| 2022-23 | 9.2% | 7.8% | 1.4% |

| 2021-20 | -3.3% | 6.7% | -10% |

| 2020-21 | 18% | 13.6% | 4.4% |

In Austrian Economics, inflation is understood as a monetary phenomenon that occurs when new monetary units are added to the existing supply. This monetary inflation is the precursor to both price and asset inflation.

Austrians also reject the idea of measuring price inflation with a single number, such as the CPI, as different asset classes respond differently to monetary inflation. For instance, industries like technology and manufacturing are less susceptible to price inflation due to the deflationary effects of increased automation and competition.

Conversely, hard assets like gold and real estate have reached record highs, as easy money tends to flow toward the most reliable stores of value.

Average Yearly Prices Increase since 2018 - Against YoY M2 and CPI

| Iphone | Median House | Money Supply Growth | CPI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Since 2018 | 2.24% | 6.8% | 7.2% | 3.1% |

*Although simplistic, the table above shows that hard assets move with monetary inflation, not CPI.

The real hurdle, or the absolute minimum that a superfund has to give it’s members is not CPI or the 3.95% 10 year, but that monetary inflation rate of 7.2%.

An increase in the required rate of return invariably brings an increase in risk. Superfunds can’t simply gamble Australians’ retirement savings on high-risk offshore tech startups, so these returns are often sought through listed equities and commercial real estate—two interest rate sensitive asset classes. This correlation significantly limits the RBA’s ability to manoeuvre and the dilemma is clear:

- Drop rates, inflate away our retirement.

- Increase rates, crash our retirement.

Bitcoin to the Rescue

You guess it, bitcoin fixes this.

Take the same example from 1991, but replace the Australian Peso with Bitcoin. In a Bitcoin world, we wouldn’t need superannuation. By simply saving 40 years of time and energy in a deflationary currency like Bitcoin, our savings alone would increase in purchasing power, eliminating the need to burden future generations for our retirement.

In the meantime, Australian superfunds should take a leaf out of a few smaller US pension funds like the Wisconsin Pension Fund and start gaining exposure to bitcoin.

A 2% allocation to a Bitcoin ETF is enough to ignite a chain reaction toward full institutional adoption. This truly scarce and desirable asset, with its low correlation to existing portfolios, isn’t just an opportunity—it’s a lifeline for the future of Australian retirees. It’s only a matter of time.

Colin Gifford

August 2024