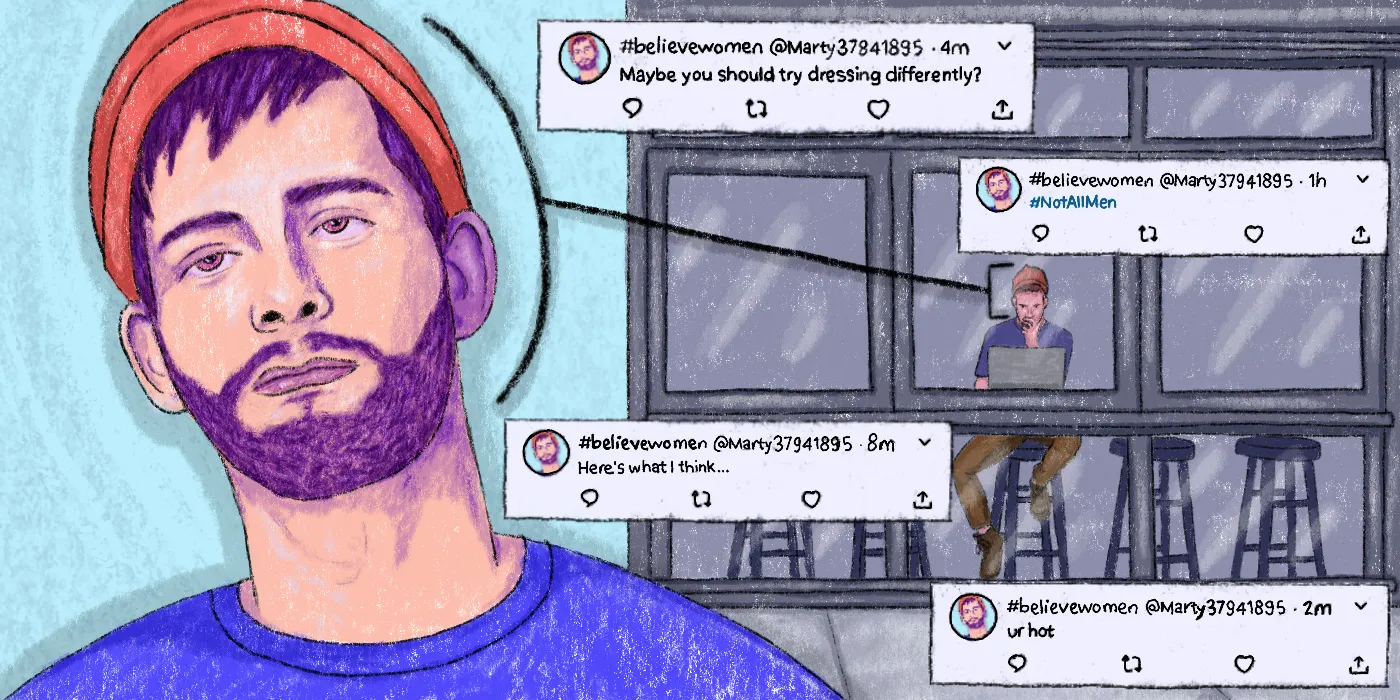

The “reply guy.” These characters aren’t merely annoying; they can actively suppress open conversation. When replies turn hostile or uncomfortable, it often leads to people withdrawing from the discussion. This isn’t an abstract concept; it’s something I’ve personally encountered.

This just came up for me in a pretty benign way, with the Wellington Cycling Group on Facebook. After being hit by a car yesterday, I hesitated to share my experience there. Why? Because I anticipated a flood of blame-shifting and negative comments. While the group is largely filled with supportive cycling enthusiasts, it also harbors a subset of anti-bicycle trolls. These individuals seem to have a grudge against cyclists and new bike lanes, possibly even being the culprits behind spikes scattered on bike paths.

In this group, the majority are wonderfully supportive, but the thought of engaging with a few disruptive trolls – both in public comments and private messages – was enough to keep me silent. My story remained untold in that space, effectively muted by the anticipated backlash. Instead, I turned to Nostr and other platforms where such anti-bicycle sentiment isn’t prevalent. While Nostr isn’t completely free of trolls, the specific anti-bicycle trolling that plagued the Wellington Cycling group isn’t an issue here.

The issue of silencing voices extends beyond traditional censorship by platforms or authorities. It also manifests in the subtle suppression by individuals or groups who discourage others from participating. This could range from blaming cyclists for urban traffic woes to inappropriate comments or doxxing.

The challenge we face is the subjective nature of what’s considered acceptable behavior. There’s no universal rule that applies to every community, whether it’s a Facebook group, a social media platform like Nostr, or any other online space. However, we can empower users to curate their own conversational environments.

On Nostr, we’ve got a protocol that is resilient and resistant to censorship by a corporation running the platform or the state. We as users can mute people we don’t want to see, without them being removed from the broader space of Nostr. But I think having the mutes be exclusively about what we see for ourselves isn’t enough.

Take Edward Snowden’s use of Nostr as an example. On Nostr, when I see a post by Snowden, I also pull in his content/user reports. If Snowden has reported somebody as a spammer, then that content is hidden behind a content warning, clearly stating, this post is hidden because it’s been reported as spam by Snowden.

When I report or mute someone, it’s a clear signal that I don’t want them in my threads. It might be beneficial to have an option to view replies from muted or reported users, but by default, I think we shouldn’t show their replies. The core idea is allowing individuals and communities to define their own conversational boundaries. Centralized platforms like twitter and instagram do let you lock replies to specific people, or your followers. They don’t show replies from people you’ve blocked either, of course.

If we don’t allow users this level of control, we’re indirectly shaping the nature of discourse. Most people prefer a friendly, welcoming space over the hostile territories of platforms like 4chan or Twitter flame wars. Most people will make the choice to retreat into spaces where they feel safe. Just like how I choose not to post some place where I’d get trolled. People want freedom, but they also want to be able to hang out with friends, free from advertising and harassment.

My experience not posting to the Wellington Cycling Group made me think about how we handle these issues on Nostr. I’ve heard from women who value Nos for its lack of direct messaging, as it frees them from unwanted interactions. Interestingly, while our roadmap considers adding DM support, this feature isn’t universally desired. It’s a reminder that shaping our online spaces is as much about what we choose to exclude as what we include.

Nostr isn’t the only place struggling with this. We see it on Twitter, Instagram, Mastodon, and Bluesky.